Indian agricultural policy has long worked with a neat fiction: a single, rational decision-maker called “the farmer” who receives information, weighs costs and benefits, and decides whether the household should adopt a new technology. That stylised figure – almost always imagined as a man – rarely corresponds to how real farm decisions unfold. In many rural households, men and women inhabit separate information ecosystems, and wield unequal influence over what finally happens on the farm.

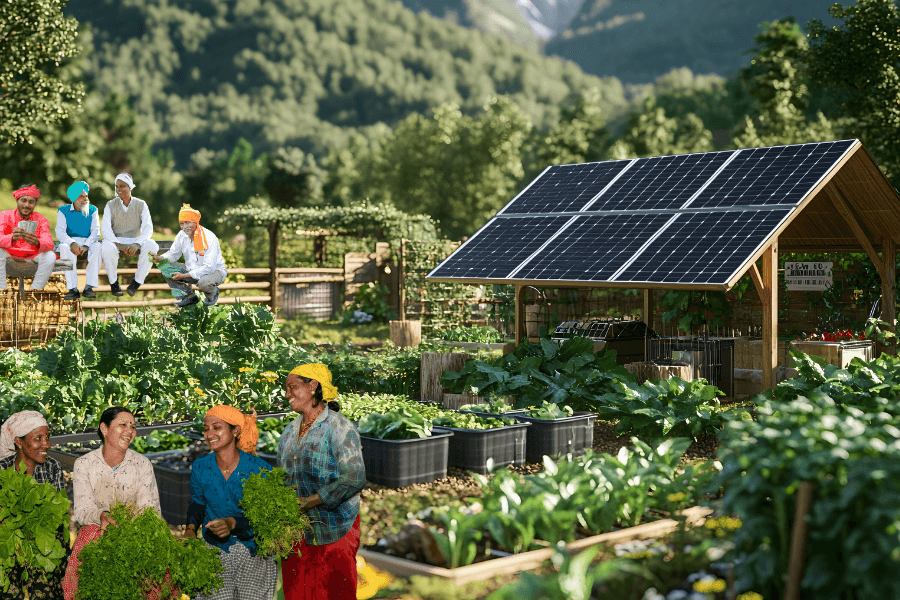

As India accelerates its shift toward water-saving, precision agriculture, understanding these dynamics is not a constraint but an opportunity. By recognising how information flows inside households, policy can unlock faster and more equitable adoption of promising technologies.

Men and Women Hear Different Signals

Laser land levelling (LLL), a precision land-preparation technique, illustrates how these internal household dynamics matter. LLL uses a laser-guided bucket to create an even field surface, cutting water use by 10–30 percent and lowering diesel consumption by around 24 percent. For eastern Uttar Pradesh’s smallholders – who operate barely 1.3 acres on average and spend about ₹1,650 per acre on diesel – these savings translate into roughly ₹350 per acre in the first year alone.

Yet the information that households receive about LLL travels through sharply gendered channels. Men’s agricultural networks tend to be smaller. Women’s agricultural networks are, on average, around 26 percent larger. These channels rarely overlap: in nearly one-third of households, only one spouse hears from an adopter. In effect, a new technology often reaches either the man or the woman, not both. This means extension efforts – advisories, demonstrations and training sessions – that communicate only with the male “household head” reach just part of the household’s learning space.

How Gendered Networks Shape Demand

A useful way to track shifts in interest is through willingness to pay (WTP) – a straightforward measure of how much a household would spend on LLL services. As households observe other adopters or gain experience, their WTP shifts accordingly. On average, it increased by ₹117 over a year, suggesting genuine learning. But this learning diverges sharply by gender.

When men are connected to even one farmer who has used LLL, their household’s demand rises by an WTP equivalent of about ₹88. When women have similar connections, demand falls by around ₹65. Among relatively better-off households, the contrast is even stronger, with demand rising by ₹129 through men’s networks and falling by ₹232 through women’s.

This divergence arises not from unequal access to information – women are often better connected – but from different interpretations. Men tend to amplify positive experiences. Hearing from a farmer who saved water and diesel boosts their enthusiasm; disappointing experiences barely register. Women, by contrast, are more attentive to downside risks. When the family is not poised to benefit much from LLL adoption, women are able to put brakes on the family’s decision to adopt. And crucially, women’s reactions are driven mainly by stories from “non-benefiting” adopters – farmers who saw limited savings – whereas men respond primarily to benefiting adopters.

Another part of the explanation lies in bargaining power. Women’s information influences the final decision only when their voice is recognised. In roughly 64 percent of households, women report that men value their opinions on agricultural matters. In these cases, women’s network-induced learning materially shifts choices, especially when their networks report disappointing outcomes. Where women’s opinions are not considered, their information – however credible – has no effect. Decisions reflect not only who learns what, but whose learning can shape action.

How Risk and Rewards Shape Learning

Household income and potential gains strongly condition how information is absorbed. Among poorer households, tight budgets and low risk-bearing capacity mute the effects of social learning altogether: even convincing stories of success do little to offset the fear of a costly mistake. They are not sceptical, just unable to experiment.

Among better-off households, where financial margins allow trial and error, learning from others becomes far more influential, though in characteristically gendered ways. Men tend to amplify positive experiences and pull the household toward experimentation, especially when the potential savings from LLL – such as in high diesel-use situations – are substantial. Women, by contrast, remain attentive to downside risks and their caution becomes more decisive when expected gains are modest or uncertain.

In low-benefit settings, a single disappointing outcome in a woman’s network can significantly reduce household demand, particularly where her opinion carries weight. These patterns show that adoption hinges not only on access to information but on how households balance the risks and rewards of trying something new.

Policy Needs a Household Lens

The first implication is the need for extension to target both information circuits within the household. Relying solely on male farmers as conduits of information is analytically flawed and operationally limiting. Men and women consult different people, hear different stories and think about agricultural risk differently. Extension efforts that deliberately engage both networks – through farmer groups and demonstrations for men, and women’s collectives, self-help groups or kin networks for women – offer a more balanced and complete information flow.

A second implication is that women’s access to information must be matched with a degree of decision authority. India’s investments in women-focused extension, digital advisories and self-help groups have broadened access, but information without agency rarely changes outcomes. Recognised stakes – secure land rights, defined roles in farm or water committees, or control over specific farm tasks – convert women’s knowledge into household influence.

A third implication is that poorer households need de-risking support alongside information. In such settings, first-use subsidies, seasonal credit linked to custom-hire services, or simple risk-sharing arrangements within farmer groups can create enough room for experimentation.

A fourth implication is the importance of incorporating gendered interpretations of risk into technology promotion. Men’s tendency to amplify success stories can accelerate adoption when benefits are large. Women’s attention to downside risks prevents overestimation of average outcomes. Policy that uses both perspectives – optimism and caution – designs more grounded diffusion strategies.

A More Realistic Path Forward

India’s next decade of agricultural innovation – from precision land preparation to micro-irrigation, digital crop advice and climate-resilient seeds – will depend on how quickly new technologies spread. Diffusion will falter if policy continues to treat the household as a single actor. Technologies succeed not only because they save water or diesel but because households interpret evidence, manage risks, and negotiate choices. Recognising these dynamics is essential for faster, more inclusive adoption.

A modern extension system must move beyond broadcasting information. It must understand the household as a negotiation between differently informed actors, engage the distinct information worlds of men and women, and match information with tools that make experimentation feasible. If India can redesign its technology outreach with these realities in mind, the gains from innovation will reach farms more quickly – and more equitably – than they do today.