The Hidden Half: Why Climate Policy Misreads Corporate Carbon

Accurate climate action depends not just on cleaner energy, but on revealing the emissions embedded in how goods are produced and moved

Kamalakanta Datta: National Institute of Technology (NIT), Karnataka

Pradyot Ranjan Jena: National Institute of Technology (NIT), Karnataka

SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | SDG 13: Climate Action

Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change | Ministry of Corporate Affairs | Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI)

Climate action increasingly depends on numbers. Governments set targets, investors price risk, and firms announce progress based on reported emissions. This pipeline works on a simple understanding: emissions associated with production and consumption occur inside company gates. But, this is seldom the case.

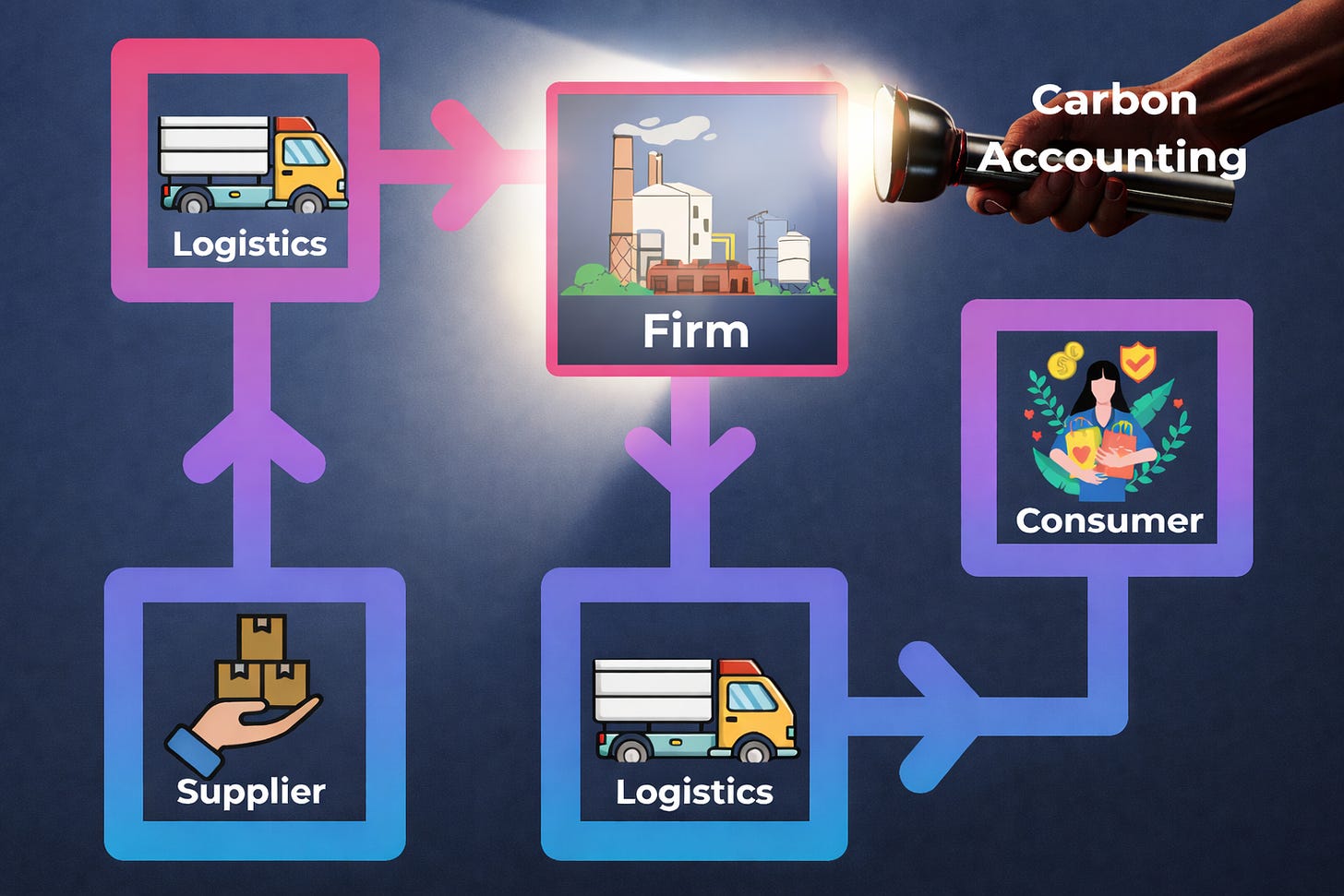

In today’s economy, firms rely on sprawling networks of suppliers, logistics providers, and downstream users – where most pollution occurs – but is only partially disclosed. When these emissions are weakly reported or omitted, firms appear cleaner than they are, industries seem less responsible than they should, and policymakers receive a distorted picture of where intervention is most needed.

Why Energy Appears to Dominate Climate Responsibility

At the global level, nearly 73 percent of greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to the energy sector. This includes electricity generation, transport fuels, heating, shipping, aviation, and all fossil-fuel combustion. Framed this way, climate change appears primarily as an energy-supply problem, with other sectors such as manufacturing, construction, and consumer goods playing a secondary role.

This framing is technically accurate but analytically incomplete. Energy use does not arise in isolation. Electricity powers factories, diesel moves raw materials and finished goods, and shipping exists because global supply chains exist. These emissions are recorded under “energy” because fuel is burned there, but they are driven by industrial demand.

How Corporate Reporting Reassigns Responsibility

This aggregation bias becomes more pronounced when national accounts are translated into corporate climate disclosures. Most companies report emissions using the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which categorises emissions into three “scopes” based on control rather than causation. Scope 1 covers direct emissions from sources owned or controlled by the firm, such as boilers or company vehicles. Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from purchased electricity. Scope 3 captures all remaining emissions across the value chain, including suppliers, logistics, product use, and end-of-life disposal.

In many sectors, Scope 3 accounts for between 70 and 90 percent of total emissions. Yet it is also the least consistently disclosed. Measuring Scope 3 requires engaging suppliers, estimating downstream use, and working with imperfect data. As a result, companies often report only fragments, rely on broad industry averages, or omit Scope 3 entirely.

India’s current disclosure framework reflects this imbalance. Under the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting requirements, Scope 1 and Scope 2 disclosures are mandatory for the top 1,000 listed firms, while Scope 3 reporting operates under a “comply-or-explain” mechanism with weaker assurance. This design does not merely tolerate under-reporting; it institutionalises it. Bloomberg data for 2024 shows that while over 1,000 Indian firms report Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, fewer than 500 disclose Scope 3 emissions. The majority of value-chain emissions therefore remain invisible on paper.

When Incomplete Disclosure Distorts Climate Signals

Partial disclosure has consequences beyond accounting accuracy. When firms report only direct and electricity-related emissions, their climate footprint appears artificially small. A food-processing company, for example, may look low-carbon even though most of its emissions arise from agricultural inputs, refrigeration, and transport. Estimates suggest that incomplete Scope 3 reporting can understate corporate emissions by up to 40 percent.

This gap enables greenwashing, where firms highlight selective improvements while ignoring larger impacts embedded in their supply chains. It also supports a quieter but growing practice: greenhushing, which simply means that some companies choose to limit climate disclosures altogether when faced with scrutiny or legal risk. Surveys indicate that roughly a quarter of global firms now avoid public climate commitments or detailed reporting. When emissions data is partial or absent, market discipline weakens and comparative assessment becomes impossible.

At scale, these firm-level choices aggregate into a systemic paralysis. Emissions disappear at the corporate level and reappear anonymously at the national level under the energy sector. Industrial responsibility is diluted twice: once through weak Scope 3 disclosure, and again through sectoral aggregation. The result is a climate narrative that overemphasises energy supply while underplaying the industrial demand that drives it.

The Policy Costs of Blurred Accountability

This accounting structure shapes policy priorities. When energy appears to dominate emissions, policy responses naturally focus on power generation, fuel substitution, and electrification. These interventions are necessary, but they are insufficient if underlying demand patterns remain unchanged.

Material choices, product design, procurement standards, and logistics architecture determine how much energy the economy requires. Electrifying transport without reconsidering freight volumes addresses fuel type but not transport demand. Expanding renewable electricity lowers emissions per unit of power, but unchecked material throughput continues to drive consumption. Weak Scope 3 reporting therefore undermines accountability in two ways. It allows firms to focus narrowly on operational efficiency while delaying value-chain interventions, and it steers policymakers toward supply-side solutions while leaving industrial systems largely intact.

What Better Scope 3 Data Can Enable

Improving Scope 3 disclosure is often treated as a technical reporting exercise. In practice, it is a governance reform. When firms map emissions across their value chains, responsibility becomes clearer and intervention more targeted. In many cases, a small number of suppliers or logistics decisions account for a disproportionate share of emissions. Visibility enables prioritisation.

Better data changes incentives. Supplier engagement becomes a climate strategy rather than a compliance burden. Procurement standards can reward lower-carbon production. Product redesign can reduce lifetime emissions. Firms that invest in these changes are no longer disadvantaged relative to competitors who appear cleaner only because emissions remain underreported.

From a policy perspective, credible Scope 3 data improves diagnosis by shifting attention toward the sources of demand that drive emissions.

Aligning Disclosure With Climate Outcomes

India’s growth trajectory makes this alignment particularly important. As supply chains expand and integrate globally, value-chain emissions will increasingly shape the country’s carbon footprint. Transparent disclosure ensures that economic expansion and decarbonisation are addressed together rather than treated as competing objectives.

Progress does not require perfect data from the outset. It requires clear direction. Mandatory Scope 3 disclosure for large firms would be a decisive first step. Clearer methodological guidance, phased expansion of coverage, and stronger assurance can follow. Equally important is linking disclosure to action. Reporting that does not inform reduction strategies risks becoming an exercise in documentation rather than transformation.

Investors and consumers also have a role. Capital allocation increasingly depends on credible climate information. When disclosures omit major emission sources, markets misprice risk and reward, undermining both environmental integrity and financial efficiency.

Making the Invisible Visible

Weak Scope 3 disclosure hides responsibility, distorts policy priorities, and raises the eventual cost of transition. Making value-chain emissions visible reconnects corporate responsibility with economic reality. It allows firms to compete on genuine climate performance, enables policymakers to target actual drivers of emissions, and complements energy transition efforts with demand-side reform.

In true sense, strengthening Scope 3 disclosure is not an administrative burden. It is a necessary foundation for a more efficient, accountable, and future-ready climate response.

Authors:

The discussion in this article is based on the authors’ ongoing work on the subject. Views are personal.