Scaling Up India’s PAT Scheme: Turning Efficiency Gains into a Long-Term Climate Strategy

PAT has trimmed emissions, now it must power India’s race to net zero.

View as PDF

Sangeeta Bansal, Centre for the Study of the World Economy, Jawaharlal Nehru University

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | SDG 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure | SDG 13: Climate Action

Institutions: Bureau of Energy Efficiency | Ministry of Power | Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change

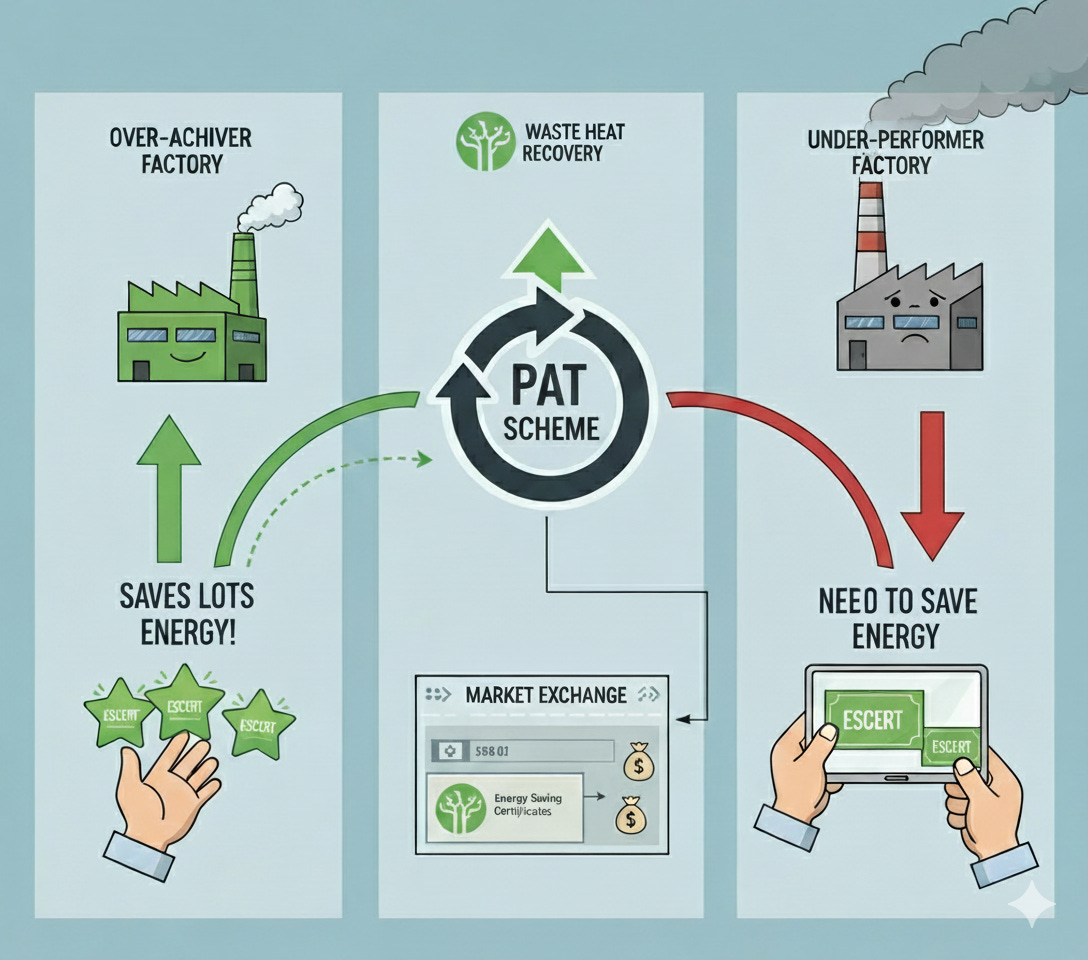

India’s energy-intensive industries account for about half of the country’s total energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Meeting climate commitments – 45 percent reduction in emissions intensity of GDP by 2030, and achieving net-zero emissions by 2070 – while sustaining growth will depend heavily on how quickly these sectors can improve efficiency. The Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme, launched by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) in 2012, is the most significant market-based mechanism in India for driving such improvements. PAT sets specific targets for reduction in energy consumption for large “designated consumers” and rewards over achievers with tradable Energy Saving Certificates (ESCerts) while requiring under performers to purchase them.

Official evaluations show measurable gains – in the first cycle, cement alone avoided an estimated 22.5 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions, with later cycles delivering cumulative savings of over 25 million tonnes of oil equivalent each year. Yet PAT’s design and implementation fall short of India’s climate ambition. Without sharper targets, better integration with all the markets, and stronger governance, the scheme risks delivering only incremental gains at a time when deep transformation is needed.

From Pilot to Plateau

PAT’s first cycle (2012–2015) covered 478 facilities across eight energy-intensive sectors – cement, fertiliser, iron and steel, aluminium, pulp and paper, chlor-alkali, thermal power, and textiles. Coverage later expanded to refineries, petrochemicals, and even the railway network. The logic was sound, that by allowing trade in energy savings, the scheme encourages investment where costs are lowest, while maintaining overall efficiency gains.

Early cycles were deliberately cautious. Baselines, often based on historical averages, understated potential savings. Many firms overachieved, creating an oversupply of ESCerts and depressing prices. Some gains came from pre-planned technology upgrades rather than PAT-driven action, underscoring the need to measure policy impact net of autonomous trends.

Sectoral results varied sharply. Cement saw major improvements from waste heat recovery and process optimisation; iron and steel from continuous casting and coke dry quenching; chlor-alkali from switching to membrane cell technology. In contrast, pulp and paper achieved little, hampered by outdated mills, finance shortages, and inconsistent utilisation. Fragmented textiles faced similar hurdles.

The lesson: a single market mechanism cannot overcome deep structural and financial barriers in weaker sectors.

Fixing Design Flaws Before Scaling Up

The credibility of PAT depends on a healthy ESCert market. In the first cycle, over 1.3 million certificates were traded – a proof that the system can work when conditions are right.

Since then, market performance has been uneven. Trading volumes have been thin in some cycles, with liquidity especially low in weaker sectors. Most compliance purchases have clustered near deadlines, blunting the year-round incentive effect. Prices fluctuate, hampered by the absence of forward trading and limited participation from new buyers.

One underlying cause is oversupply, caused by lenient targets and unadjusted baselines. This can be addressed through dynamic target setting – allowing mid-cycle adjustments if over-achievement becomes widespread, to keep price signals robust and prevent prolonged periods of low certificate value.

Another weak spot is in governance. Limited audit capacity at the BEE and state agencies, inconsistent measurement and verification (M&V) quality, and delays in ESCert issuance weakens confidence. A digital platform, linking sectoral production and energy use data in real time, could improve enforcement and transparency.

Supporting Lagging Sectors

Price signals on their own cannot address structural barriers. Ensuring the long-term sustainability of the regulation requires careful consideration of its impact on firm performance and profitability. Smaller mills in pulp and paper and SMEs in textiles lack finance for retrofits, face poor economies of scale, and lack in-house expertise for complex upgrades.

Public policy can bridge this gap through targeted interventions. One approach is to establish concessional credit lines and blended finance for efficiency upgrades. Another is to promote technology transfer programmes that bring high-efficiency equipment into domestic markets at competitive costs.

Pooling procurement of high-efficiency motors, boilers, and process controls could cut costs, particularly for small producers. In parallel, sector-specific capacity building, such as training engineers and plant managers in modern energy management systems, would ensure technology is used effectively.

Japan’s Top Runner programme offers a useful precedent, pairing mandatory targets with technical support and pooled technology deployment, helping weaker sectors catch up with the leaders.

Integrating with Other Markets and Policies

The Energy Conservation (Amendment) Act, 2022 enables a national carbon market, offering an opportunity to integrate PAT with broader emissions trading. Linking the two could boost ESCerts demand, but would require harmonising baselines, M&V, and compliance periods to avoid double counting.

Integration should go beyond carbon trading to include the Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) market so efficiency gains and renewable expansion are complementary, not competing. It should also align with state-level programmes and sectoral industrial policies so that energy savings reinforce broader modernisation and competitiveness goals.

Internationally, the EU Emissions Trading System initially struggled with overlaps between efficiency directives and emissions caps but improved once targets were coordinated across policies.

Strengthening Market Infrastructure

PAT’s market would benefit from forward and futures trading of ESCerts, enabling firms to hedge costs and plan strategically. Compliance timelines could be tailored for sectors with long investment cycles, like iron and steel. Regularly updated sectoral performance benchmarks based on best available technology, not historical averages, would keep the scheme ambitious and aligned with global best practice.

Keeping Ambition in Line With Net Zero

India’s commitment to net zero by 2070 means industrial energy intensity must fall much faster than in the past decade. PAT can be central– but only if ambition rises steadily. A published decadal tightening pathway, linked to India’s nationally determined contributions, would give industry the certainty to justify large-scale retrofits and process overhauls.

The framework can also extend beyond heavy industry. Transport fleets, large commercial buildings, and mid-sized manufacturing such as textiles could be brought under the PAT, locking in gains before demand growth makes improvements costlier – a mistake seen in countries that acted only after rapid industrial expansion. Another sector that needs to be brought under policy framework is SMEs that contribute around 33.4% of India’s manufacturing output. The framework should find ways to bring energy efficiency in this sector.

A Tool Worth Upgrading

The first decade of PAT proved that efficiency gains can be measured, verified, and traded in India’s industrial context. The next must show that such trading can drive structural change. That means tightening targets dynamically, improving market infrastructure, integrating with other policy instruments, and supporting lagging sectors with finance and technology.

If strengthened along these lines, PAT could shift from a compliance mechanism to a cornerstone of India’s industrial decarbonisation – cutting emissions, saving energy costs, and boosting competitiveness in one integrated policy move.

View as PDF

Authors:

The discussion in this article is based on her co-authored research published in Energy Economics (Volume 113). Views are personal.