View as PDF

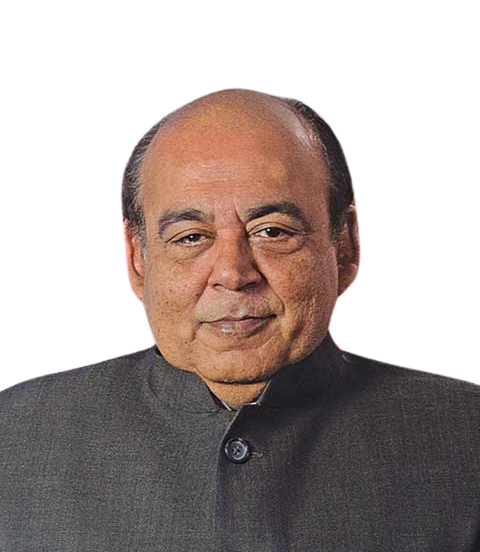

Mr. Sanjiv Kohli is a retired Indian Foreign Service officer (IFS) with over three decades of experience in diplomacy, crisis management, and economic engagement. He has served in Kuwait, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Qatar, Tanzania, Serbia, and New Zealand, and held senior roles in the Ministry of External Affairs, including as Head of the West Africa Division.

Over his career, he has worked on deepening India’s partnerships across the Gulf, Africa, and the Pacific, and on strengthening people-centric dimensions of foreign policy–diaspora engagement, health diplomacy, and capacity building.

In this conversation with The Policy Edge team, Ambassador Kohli reflects on choices made under pressure, the evolving nature of the Indian Foreign Service, and lessons that resonate far beyond diplomacy.

You moved from engineering to the uncertainties of diplomacy in the late 1980s, when foreign policy was still seen as somewhat distant from everyday governance. How did those early years shape your understanding of the ways India’s diplomacy connects with domestic policy?

When I joined Foreign Services in 1988, diplomacy still seemed a closed world – largely narrative-driven by the political class and governed by hierarchy and distance. The real shift came a few years later, with liberalization. Suddenly, we were talking about trade, investment, and intellectual property in the same breath as sovereignty. The choices we made at home – on reforms, IT, or energy – started shaping the questions we faced abroad.

I remember thinking then that India didn’t yet have the institutional vocabulary for economic diplomacy. We learned by doing – whether it was negotiating with investors, explaining reforms abroad, or reassuring partners that India’s democracy would sustain openness. Diplomacy taught me that judgment, not formulas, ultimately shapes policy. This convergence of systems and human behaviour was fascinating.

You were in Kuwait when the Iraqi invasion upended everything. How did those chaotic weeks reshape your understanding of responsibility in government service?

It was an extraordinary period: one of those moments when training meets history. I was meant to be studying Arabic; it wasn’t a crisis posting. But I found myself part of an evacuation mission for roughly 170,000 stranded Indians, many without documents, desperate to get home. There were days when no instruction could reach us in time. Do you wait for formal clearance or act to save lives? That is the kind of dilemma no manual prepares you for.

We had to establish communication lines, negotiate safe passage through Jordan, and improvise logistics without precedent.

I remember standing on the Jordanian border, watching convoys of buses filled with families who had lost everything. The question was simple: how do you move thousands safely, without triggering panic or conflict? It was India’s largest civilian evacuation, and every small decision mattered. That experience stripped diplomacy of its ceremony – it became about clarity, courage, and care under pressure.

Years later, when the evacuation was dramatised in the film Airlift, it struck me that the episode had entered public imagination – even if the movie took artistic liberties. Diplomacy was seen as problem-solving, not just protocol.

From the Gulf to Africa and New Zealand, your assignments span very different worlds. How does a diplomat keep India’s core interests intact while tailoring policy to such contrasting political and cultural settings?

Every posting tests your ability to translate New Delhi’s priorities into local idioms. Mobilising investments, steering trade agreements, building perception, and scanning political economy is always a work in progress. But there are layers of variations across postings as well. In the Gulf, your work is human – managing labour rights and crises involving Indian workers. In Africa, history is an asset; goodwill from the Non-Aligned Movement opens doors, but you must convert that into partnerships in health, education, and agriculture. In New Zealand, the challenge was narrative – explaining a new India to a society that still pictured the old one.

Foreign policy has some fixed variables: India’s security, stability, and access to opportunity. But execution demands agility. Ambassadors are, in a sense, policy entrepreneurs – they interpret the brief, improvise, and reconcile contradictions. The measure of success is not whether you follow the line, but how well you adapt it without losing coherence.

There are several cases of human crises involving Indian emigrants and requiring Embassy support for resolution. How did you navigate such cases within the hard calculus of bilateral ties?

The diaspora is both India’s soft power and its mirror. Whether in the Gulf or Africa, there are instances when you deal with real, human crises – workers detained or stranded without cause. The diaspora expects both protection and pride, but the dilemma is constant: raise the issue firmly and risk straining ties, or tread softly and risk appearing indifferent. Neither option is wrong; both have costs.

Host countries hold both economic and political leverage, and their systems can be complex – opaque regulations, multiple desks, and shifting responsibilities. Diplomats must build credibility and find points of influence within that landscape.

In Africa, our leverage often came from trust and health diplomacy. Offering medical visas or training opportunities-built goodwill that statistics cannot capture. In the Gulf, where the trade balance and energy dependence weigh heavily, empathy has to be strategic.

I recall one episode where an Indian national was detained in an African country with little justification. The official process required us to go through their Ministry of External Affairs – across several desks – and then another Ministry. Ten days passed with no progress. We decided to quietly signal our leverage through a minor delay in a set of medical visa approvals. Soon, the release was processed.

The key lesson is that engagement cannot be episodic or sentimental. It must rest on a calibrated advocacy – a blend of diplomacy and duty.

Diplomatic cables and formal channels are often viewed as procedural exercises. From your experience, how do persuasion and trust move a decision in New Delhi, and what separates reporting that informs policy from routine paperwork?

It’s far from linear. The formal route is there – reports to the territorial division, joint secretaries, foreign secretary, and so on – but effectiveness depends on clarity and credibility. A well-judged one-page note can do more than a thick brief.

In emergencies, parallel channels open – hotlines to key ministers. But even then, what matters is not access, it’s trust. If your judgment has proved reliable, your advice carries weight. In that sense, diplomacy runs on both systems and relationships.

It is important that we write or communicate with purpose, not volume. What you omit can be as consequential as what you include. Precision is not just a stylistic choice; it’s a safeguard against misinterpretation.

After nearly four decades in public service, watching diplomacy shift from protocol to problem-solving, what should the next generation of policymakers – inside or outside foreign affairs – understand about exercising judgment when the rulebook runs out?

First, understand that foreign policy is no longer foreign. Every domain – technology, climate, health, data – is cross-border. Policymaking today demands fluency in multiple languages: of economics, security, and human rights. The silos we inherited no longer serve us.

Second, cultivating judgment is critical. Institutions can give you structure and precedent, but not wisdom. Many times in my career – whether during the evacuation, or in negotiations where one wrong word could change tone – I realised that leadership means acting responsibly before instructions arrive.

If I could add a third, it would be curiosity. When I look back, learning Arabic turned out to be one of my most consequential decisions. It taught me that diplomacy begins not with statements, but with listening. And that holds true for any public servant.

View as PDF

Views are personal.