India’s Manufacturing Bottleneck: The Right to Exit

India’s industrial future hinges not only on entry incentives but on the overlooked challenge of orderly exit.

View as PDF

Shoumitro Chatterjee, Johns Hopkins University | Centre for Economic Policy Research

Kala Krishna, The Pennsylvania State University | Econometrics Society | National Bureau of Economic Research | International Growth Centre | CESifo, Germany

Kalyani Padmakumar, Florida State University

Yingyan Zhao, George Washington University

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institution

Institutions: Reserve Bank of India | Ministry of Finance

India has long looked to manufacturing as the engine of broad-based prosperity. The sector is expected to absorb surplus labour from agriculture, provide stable middle-class jobs, and power exports in the way East Asia once did. Yet despite ambitious policies and waves of investment incentives, manufacturing has not generated the momentum many envisioned.

The reason goes beyond familiar bottlenecks like infrastructure or skills. It lies in a less visible weakness: firms that do not exit when they should. Unlike economies where failing businesses exit swiftly, freeing up resources for new ventures, India remains weighed down by “exit barriers” – the legal, administrative and institutional frictions that make winding up a company and redeploying its assets exceptionally difficult. Knowing that exit, if desired, will be difficult, makes firms less willing to enter so that exit barriers become entry barriers.

Unless India stops dragging dead weight from its industrial past, it will struggle to move forward.

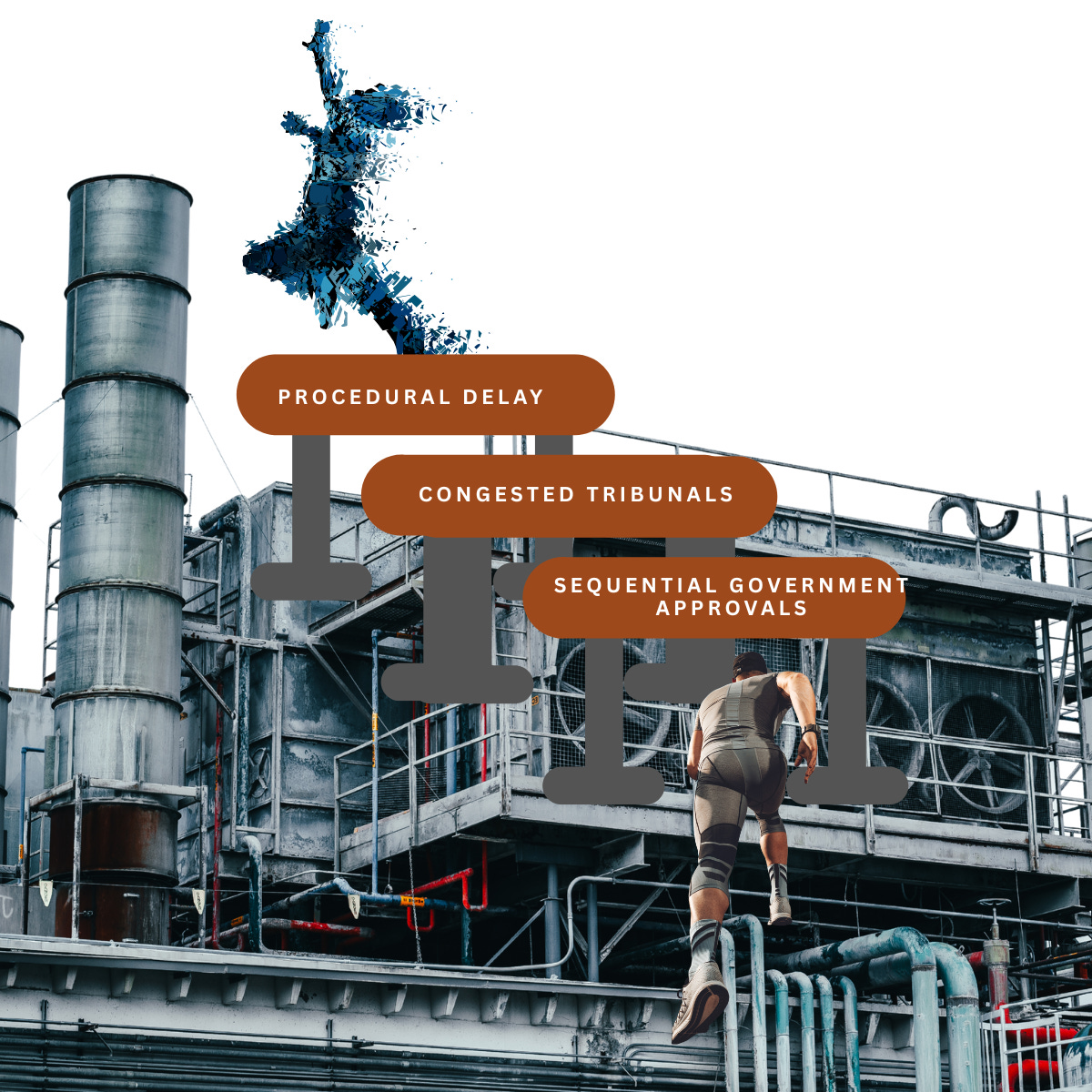

Why Firm Closures Take Years

While firms in Singapore can close within a year, and in Germany or the UK, within under two years, in India, the process stretches to an average of 4.3 years. Much of this delay comes from navigating clearances across multiple government departments. Roughly 2.8 of those years are lost to pending tax refunds, provident fund settlements, and other approvals.

The result is widespread “dormancy.” More than a fifth of registered Indian firms no longer operate but remain on the books – with unpaid loans and frozen assets.

Labour and Bankruptcy Laws That Linger

Part of the problem lies in the way India’s laws evolved. Labour regulation continues to be shaped by the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947, which requires firms with more than 100 workers to obtain government approval before retrenching staff. This process is slow, discretionary, and frequently contested in court. As of 2020, Indian courts were handling more than 100,000 pending labour cases – 40 percent of which were unresolved for over a year.

Bankruptcy reform has also struggled. Successive frameworks – the Debt Recovery Tribunals in the 1990s, the SARFAESI Act of 2002, and the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) of 2016 – were all designed to expedite corporate restructuring and protect creditors. But congested tribunals, uneven implementation, and repeated re-litigation have dulled their effect. The IBC was a breakthrough in principle, but in practice, deadlines often get stretched well beyond the intended 270 days, leaving both creditors and owners in limbo.

When States and Courts Block the Exit

Even when statutes are clear, administrative discretion slows things down. Procedures vary sharply across states, depending on how officials and courts interpret the rules.

Consider a textile factory in Maharashtra that is seeking to close due to sustained losses. Owners must clear tax, provident fund, and land disputes across uncoordinated offices. If unions contest layoffs or a land dispute emerges, the process can drag on for years – often beyond the owners’ planning horizon.

The case of Nokia’s plant in Tamil Nadu offers a striking example. Once India’s largest mobile phone factory, employing over 20,000 workers, it became entangled in overlapping tax and labour disputes after operations ceased. It took six years before its assets could be transferred. For employees, this meant prolonged uncertainty and lost opportunities for reskilling. The case showed both the human costs for workers and the economic costs of immobilised assets.

Why Exit Matters for Growth and Inclusion

The inability to close firms efficiently undermines growth. International evidence shows that where exit is easier, new firm entry is higher. India confirms the pattern. States that allow smoother exit see stronger competition, more entrepreneurs, and faster productivity growth.

The difference is measurable. In high-performing states, exit rates are nearly double those of lower-performing ones, and productivity among older plants is about 22 percent higher. Entry and exit are closely correlated: states with higher exit also see more entry, underscoring how barriers to closure suppress entrepreneurial dynamism.

Sectoral variation matters too. Exit barriers weigh most heavily in labour-intensive industries, where firms face both stricter labour regulation and higher compliance costs.

For workers, barriers to exit provide only an illusion of protection. Jobs linger in unproductive firms, often at stagnant or slow-growing wages, while opportunities for better employment are missed. The real safeguard for labour is a dynamic economy where new firms expand and displaced workers are absorbed into better jobs.

The fiscal consequences are equally serious. Dormant firms inflate non-performing loans in public sector banks, which dominate the manufacturing finance sector. Taxpayers ultimately bear the cost, either through recapitalisation packages or through reduced government capacity to invest in infrastructure, education, and health.

The Economics of Exit

Economists describe these costs as “exit frictions” – the delays and expenses that make it hard for a business to shut down. These are weighed against a firm’s “scrap value,” or the worth it can recover when leaving the market. In India, frictions are high and scrap values are low, so firms tend to linger rather than close.

The cost is not abstract. If India raised its exit rate to even 70 percent of the US level, manufacturing’s contribution to GDP could rise by 13 percent and productivity by 3 percent.

The reform scenarios are striking. Loosening labour laws to reduce firing costs could raise value added by around 18 percent but reduce employment by 14 percent, as firms restructure aggressively. By contrast, improving institutional exit conditions – cutting judicial backlogs and administrative delays – could lift value added by 19 percent and employment by 8 percent. Doing both together produces the strongest results: value added up 38 percent and employment up 5 percent.

For policymakers, the message is clear: sequencing matters. Reforming institutions first cushions the employment risks of labour reform, delivering both growth and jobs.

How to Make Exit Work

India has mastered the art of entry – designing incentives to attract new projects and industries. The harder task is designing exits that are efficient and inclusive.

Significant improvements can be achieved by streamlining procedures. Today, approvals are handled sequentially – tax, provident fund, land, environmental clearance – each waiting for the one before it. If processed in parallel through a digital “one-stop exit window,” years could be cut from the timeline.

Labour regulation does not need wholesale dismantling but greater clarity. Mediation should be encouraged as a first step to reduce the burden on courts. Rules on when government permission is required – for example, when firms employ more than 100 or 300 workers – should be transparent and time-bound, giving certainty to both firms and workers.

Bankruptcy institutions need more capacity. Dedicated benches for complex cases, modern case management, and a larger cadre of insolvency professionals would improve both speed and outcomes. State governments could complement these efforts with “exit facilitation cells” to guide firms, resolve bottlenecks, and monitor timelines.

Reform must be matched by support for workers. Retraining and targeted assistance are essential. Without this, exit reform risks being seen as anti-labour; with it, reform can be framed as pro-opportunity, equipping workers for the jobs of tomorrow.

Responsibility is widely shared. The Ministry of Labour and Employment, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, the Department of Financial Services, public sector banks, state industry departments, and the judiciary all have roles to play. Coordinating across them will be as important as any single reform.

Renewal through Closure

If India can unlock exit, it will unleash the cycle of renewal that keeps every modern economy alive: new firms rising, old ones leaving, and resources flowing to where they are most productive. That is the missing ingredient for manufacturing dynamism.

The choice is clear. India can hold on to outdated firms, risking a manufacturing sector weighed down by zombies. Alternatively, it can adopt the discipline of exit, thereby clearing the path for growth, jobs, and genuine industrial transformation.

View as PDF

Authors:

The discussion in this article is based on the authors’ working paper on the subject. Views are personal.