Designing Development: Mission Samriddhi’s Experiment in Rural Transformation

A corporate technologist’s journey to India’s villages reveals how design thinking, not charity, can reshape rural development

View as PDF

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | SDG 16: Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions

Institutions: Ministry of Rural Development | Ministry of Panchayati Raj

When Ram Pappu left his corporate career, few around him understood why. With stints at IBM, Microsoft, and Standard Chartered, and an MBA from Canada, he had built what many would call a perfect global trajectory. But something, he says, “didn’t quite add up.”

“I was successful, but not fulfilled,” Ram recalls. “That restlessness became louder than any promotion or title.”

He returned to India and began volunteering for a foundation supporting rural schools and this brief engagement soon turned into a calling.

“When I travelled to villages,” he says. “I realised development isn’t about giving – it’s about enabling. It’s about dignity, opportunity, and structure.”

The idea found direction in 2016 when Ram met Arun Jain, the visionary founder of Polaris Software, whose work has long bridged business innovation and social purpose. Years before corporate social responsibility became a norm, Arun Jain had launched the Ullas Trust in 1998 to mentor adolescents in government schools, nurturing aspiration through exposure and confidence-building. He later founded the School of Design Thinking, a platform that brought empathy and creativity into problem-solving for organisations and individuals alike.

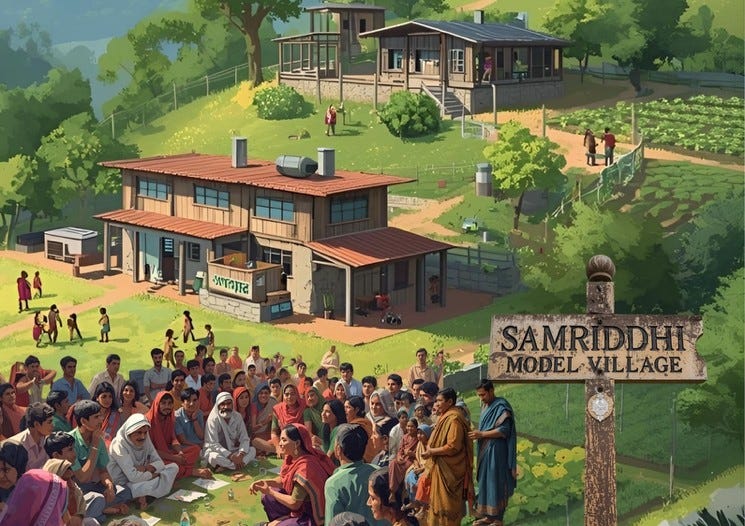

Mission Samriddhi was a natural extension of this philosophy – Arun Jain’s effort to channel private purpose into public value through design-led rural transformation. Drawn to its vision, Ram joined the initiative and now serves as its Executive Director.

Designing Rural Change

When Mission Samriddhi was taking shape, the team launched a series of design-thinking workshops across rural India, mapping patterns of deprivation and aspiration.

“We asked a simple question – if rural India were a start-up, what would its design look like?” Ram recalls.

The result was a five-pillar model for transformation: personal, social, economic, ecological, and institutional development. Over time, this evolved into a 150-indicator framework – a roadmap to measure progress not only in income or infrastructure, but also in confidence, participation, and local governance.

This framework underpins Mission Samriddhi’s Cluster Development Programme (CDP) – a five-year initiative implemented through value-based NGOs across clusters of villages. Each cluster, typically about five panchayats, is supported by trained resource persons who facilitate monthly development dialogues and annual self-assessments with villagers.

“Every cluster is a living lab,” Ram says. “We don’t run projects; we build capacity for communities to run their own.”

Mission Samriddhi now operates in 7 states, 22 districts, and 320 Gram Panchayats, reaching nearly 2.4 lakh households and a population of 9.5 lakh. It has trained and capacitated over 9,500 panchayat members.

“The achievement isn’t the number,” Ram says. “It’s in the people behind them – those who’ve begun to see themselves not as beneficiaries, but as changemakers.”

Learning by Seeing

The heart of the programme lies in the Samriddhi Yatra – a design dialogue on the move. These yatras, which help villagers see how peers have improved farming, governance, or sanitation, have so far taken 100s of elected representatives and village leaders to model sites.

“When a farmer from Bundelkhand sees a farmer in Dharmapuri using solar pumps or running a farmer-producer company, he doesn’t need a lecture,” Ram explains. “He sees what’s possible.”

Through these yatras, communities identify their priorities through weighted problem-solving sessions – a participatory process that blends data, empathy, and experience. Ram believes this turns development from an externally driven project to an internally motivated journey.

“Villagers score their own priorities, debate trade-offs, and agree on what really matters,” he adds.

One such Yatra – by over five dozen men and women from Uttar Pradesh to Kerala – became a turning point. Seeing how self-help groups there built discipline and dignity into daily life, they led a quiet current of change in their own villages – ending night weddings, curbing alcohol use, and enforcing community bans on child marriage. Their effort also revived local volunteerism, with villagers organising clean-ups and tree-planting drives on their own.

“These are not external interventions,” Ram stresses. “They are collective realisations.”

Bridging the Miles

Mission Samriddhi sees itself as a bridge rather than a delivery agent.

“We co-fund and capacitate credible local organisations that already have the trust of the community,” Ram clarifies.

This model allows flexibility and scale. Its success drew UNICEF to collaborate with Mission Samriddhi during Phase 2 of COVID-19 to strengthen Panchayat preparedness and response. IndusInd Bank and UNICEF have launched a climate-resilience partnership with Mission Samriddhi, across 75 panchayats in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu, focusing on disaster readiness, natural-resource management, and sustainable livelihoods. Collaborations with IIT Gandhinagar’s Water & Climate Lab bring cutting-edge, data-driven insights to farmers – providing microclimate forecasts and crop advisories informed by advanced research on hydrology, climate systems, and extreme weather.

Trust as Infrastructure

For Ram, though, the real infrastructure of development is invisible.

That is why Mission Samriddhi partners with long-established organisations like Banwasi Seva Ashram in Uttar Pradesh, SeSTA in Assam, Gramin Samasya Mukti Trust in Maharashtra, IRA in Betul , CYSD in Odisha, Gramium in TN and Prem Samriddhi Foundation in Rajasthan whose credibility anchors the work in local culture. Many of these partners have contributed to the ₹24 crore in convergence funding that Mission Samriddhi has mobilised across states.

Each partnership is vetted through rigorous due diligence and accompanied by impact assessment. Yet Ram is candid about the limits of what can be achieved.

“On the surface, indicators improve – health, schooling, income. But deep issues like caste-based inequality and gender inequality don’t disappear quickly. Development is a long conversation, not a campaign,” Ram argues.

Education, Equity, and Everyday Change

Among the most persistent challenges, Ram points to education.

“We still teach as if children will only take exams, not build livelihoods,” he notes”

Mission Samriddhi’s education work re-energises learning through colour-coded textbooks, science kits, and teacher training that link curriculum with local life. The emphasis, Ram says, is on curiosity and confidence, not rote.

“You can’t teach equality and habits in the classroom if the community doesn’t live it outside,” he says.

The programme now reaches over 27,000 children, with measurable gains in reading and science scores – in some places rising by nearly 50 percent.

To sustain this, Mission Samriddhi is exploring partnerships with spiritual value-based organisations like Brahma Kumaris, whose work on discipline, purpose, and inner transformation strengthens what Ram calls “the software of change.” Their workshops help build confidence and collective resolve before larger programmes begin.

Natural Farming, Natural Leadership

Ram sees the cycle of chemical farming – debt, dependence, and exhausted soil – as one of rural India’s deepest structural traps. Through demonstration plots and peer farmer networks, Mission Samriddhi encourages a gradual shift towards natural and climate-resilient farming.

The transition begins with a few early adopters who experiment on small plots and share results with neighbours, creating a chain of local champions. Farmers are supported through community tool banks – women-friendly equipment, soil testing, and collective seed and compost preparation.

Over 6,900 farmers have already transitioned to natural methods across 7,200 acres, conserving nearly 183 million litres of water and improving household nutrition.

“When a farmer reduces dependence on costly external inputs,” Ram explains, “he begins to recover not just his soil, but his confidence – along with better health for his family and the chance to market his surplus produce.”

Scaling with Conscience

For Ram, the question is not whether India can scale rural development, but how. Behavioural change – the shift from dependency to participation – lies outside official metrics.

“We have schemes, funds, and institutions. What we need is convergence and conscience,” he says.

The missing link, in his view, is what Mission Samriddhi calls Development Accelerators – bridge organisations that turn design into delivery. They connect government schemes with local NGOs and communities, aligning funding, building capacities, and tracking progress across departments. They are the architecture that makes convergence work on the ground.

India’s policy ecosystem, Ram argues, must now reward design, not just delivery. “The irony is that the government funds hardware,” he smiles, “but what really works is heartware.”

View as PDF

Ram Pappu is the Executive Director of Mission Samriddhi. All the details are based on his account and have been approved for publication. This piece was prepared with assistance from Ms. Vardhini, a member of the editorial team at The Policy Edge.