Childcare Leave in Bihar: A Good Policy Undermined by Poor Delivery

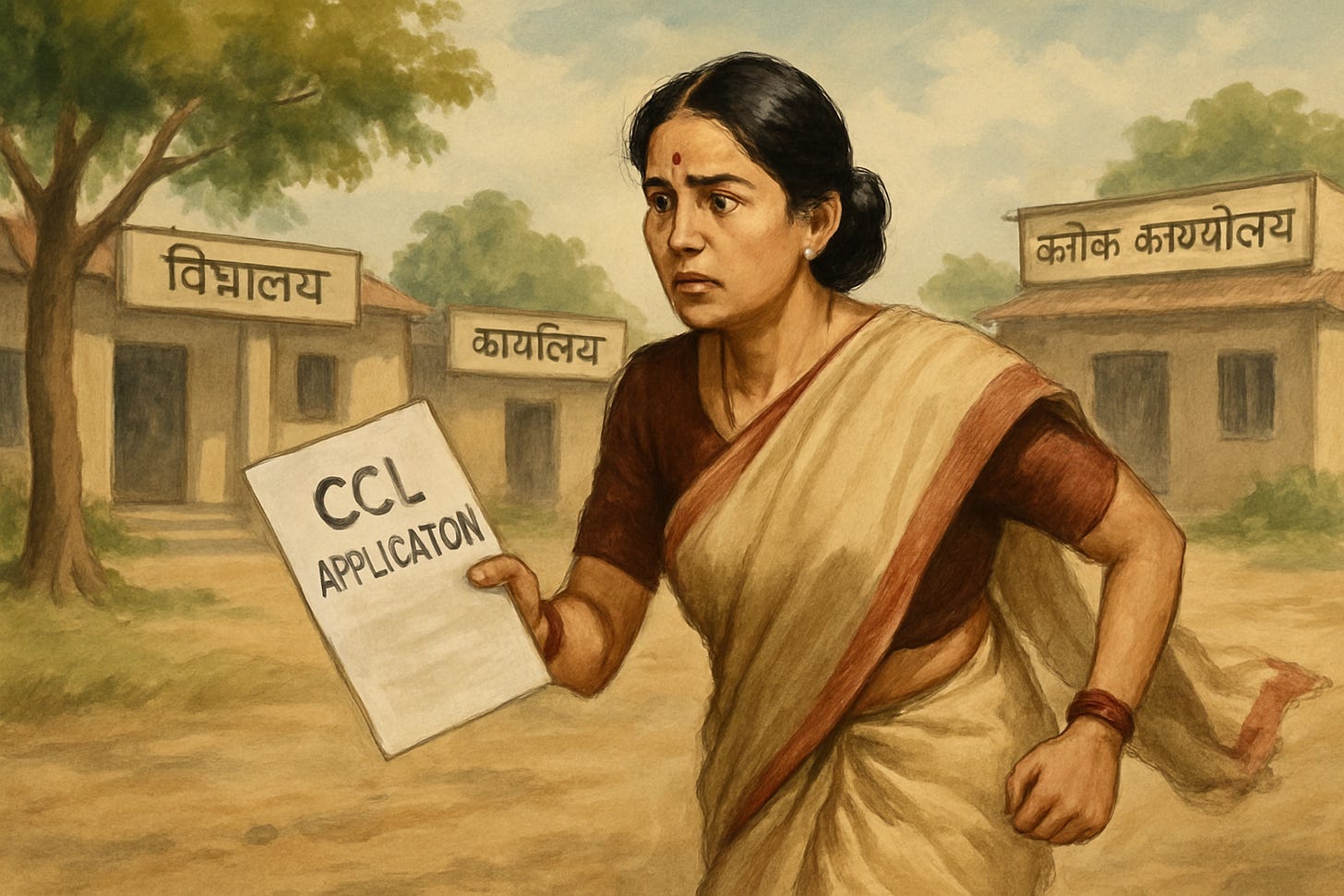

A teacher’s journey through delays and a failed digital service reveals why implementation and not just intention shapes the impact of public policy.

View as PDF

SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

Institutions: Department of Education | Government of Bihar

The Bihar Government’s decision to extend Child Care Leave (CCL) to women teachers is a welcome step that offers much-needed support to mothers in the state’s public education system. Under this provision, eligible teachers can avail up to 730 days (two years) of leave to care for their children. This policy shift is significant; however as Arundhati Kumari, a government middle school teacher found, the gap between eligibility and implementation remains wide.

For Arundhati, the dream of becoming a teacher took root early - growing up in Bihar, she always saw education as both a calling and a way to serve. After clearing the Bihar Public Service Commission (BPSC) exam, she joined the government school system and has spent the last decade teaching in the classroom. This June, her responsibilities as a mother took precedence and she applied for CCL to be with her son, who is preparing for his board exams in another city. Alone and overwhelmed, he has been finding it hard to manage without her.

Gatekeepers, Not Guidelines

Arundhati had hoped the process would be straightforward. After all, the Department of Education had issued a clear directive allowing CCL for all categories of teachers. Recent media reports had even pointed to the government’s new mandate: all leave applications were to be processed through the e‑Shikshakosh portal, pointing to efficiency and transparency. When she applied, that hope fell apart - the portal wasn’t functional, and what was meant to be a streamlined process turned into a confusing, manual maze.

Her school principal was supportive and approved the application readily. Once the file moved to the Block Education Office and then to the district office, the path became less predictable.

“Each time, it was something new; another paper, a different signature,” Arundhati told The Policy Edge. “I kept doing what they asked, but it never seemed to end.”

What Arundhati encountered is common across many local offices: informal checkpoints that exist beyond the written rules. The most consequential interaction isn’t with a senior officer, but with a clerk.

“At first, he kept sending me from one office to another, asking for different approvals,” she said. “Then, he hinted that things would move faster if I took care of chai-pani,” she added, referring to the local shorthand for an informal payment.

Arundhati didn’t give in. Instead, she kept returning to the office day after day, explaining her situation patiently.

“After about two weeks, he finally listened,” she recalled. “He said, ‘Aapka kaam ho jayega, Madam.’”

The leave eventually came through nearly two months after she first applied. It was her persistence, not the system, that moved the file forward.

Delivery Defines Dignity

“It wasn’t kindness that I wanted, it was clarity,” Arundhati said.

Her words shift the focus from individual empathy to institutional accountability. This isn’t a story about a helpful clerk doing a favour; it’s about a citizen having to navigate a broken, discretionary system to access a right she already had. It reveals how much public service delivery still relies on informal checkpoints and personal persuasion, rather than clear rules. Arundhati wasn’t asking for a favour; she was demanding dignity.

The Next Step is Transparency

This inclusion, though delayed, signals a recognition of the dual roles that many women in education balance, and more broadly, of caregiving as legitimate labour. It affirms the importance of a mother’s presence during critical stages of a child’s education and well-being, and the need for institutional support to make it possible.

“I have seen so many women leave their jobs when they become mothers; especially when children are in their teenage years. CCL will help retain teachers in the workforce.”

Yet Arundhati’s relief comes tempered with realism.

“The Centre introduced CCL in 2008. It has taken more than fifteen years for us to be included. But now it will be helpful if the process is made more transparent so teachers can truly benefit from it,” she said.

Bridging Policy and Practice

Arundhati’s story shows a well-designed policy doesn’t always translate into practice. The framework may be in place, but delivery remains uneven.

“There’s no central checklist, no digital tracking, and no clear escalation channel if delays happen,” she noted.

Her experience is a reminder that good policies must be supported by accessible systems; not just in urban centres, but in every block and school office where they are meant to be implemented.

The comprehensive e‑Shikshakosh portal holds potential to streamline the leave application process, but when the digital system doesn’t work, that promise rings hollow. Technology must be more than symbolic; it should actively reduce friction for users. Especially today, when AI and digital tools are simplifying administrative processes across sectors, public service delivery must keep pace. Child Care Leave is more than an administrative provision; it is a recognition of care as a public good. When a right is easy to access, policy begins to honour both work and dignity.

View as PDF

The teacher’s identity has been anonymised at her request. All other details are based on her account and have been approved for publication. This piece was prepared with editorial assistance from Ms. Srishti Shankar, a member of the editorial team at The Policy Edge.