Anaemia Among Indian Muslim Women: A Structural Health Divide

One in two Muslim women are anaemic - a silent crisis hiding in plain sight. Sharper and more inclusive policy design is needed to ensure health gains reach those most often overlooked.

View as PDF

Zeenat Hashmi, IIT Bombay, India.

Ashish Singh, IIT Bombay, India.

SDG 3: Health and Well-Being | SDG 5: Gender Equality | SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

Institutions: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | Ministry of Women and Child Development

Despite decades of public health investment and economic growth, anaemia remains one of India’s most persistent and underestimated health challenges. Among the most affected are Muslim women of reproductive age (15-49 years), whose anaemia prevalence rose from 48.77 percent in 1998 to 55.6 percent in 2021. This troubling trend stands in sharp contrast to India’s broader development gains; yet rarely featured in policy conversations.

This is more than a nutritional or medical concern; it reflects deep social inequality. Data from four rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), covering over two lakh Muslim women, reveal this layered story. Muslim women carry a quiet burden; often missed by targeted programmes and broad statistical categories alike. Within this group, anaemia disproportionately affects those who are poor, rural, less educated, and socially marginalised.

How can policy negotiate this burden? Recognising anaemia as a layered social burden, on top of it being a nutritional or medical issue, and adapting the existing schemes such as the Anemia Mukt Bharat (AMB) and Poshan Abhiyaan to these layered realities can go a long way.

A Story of Disparity, Not Just Deficiency

What is striking about anaemia among Muslim women in India is not just how widespread it is, but who suffers the most - and why.

Age is one of the sharpest dividing lines. NFHS-5 shows that young Muslim women, especially those aged 15 -19, face the highest vulnerability. This age cohort is critical: nutritional deprivation here affects not only individual health, but the health of future generations that are often overlooked in policy design.

Caste and education add another layer. SC/ST Muslim women show some of the highest rates, exceeding 56 percent. Education shows some protection, but even among better-educated Muslim women, prevalence remains above 51 percent - suggesting that schooling alone cannot overcome barriers like poor diet, gender norms, or healthcare exclusion.

Economic status deepens the divide. In NFHS-5, the Poor-to-Rich ratio, comparing prevalence among the poorest and richest quintiles, stood at 1.41 overall and even higher among women aged 40-49. The Concentration Index, which measures whether a condition disproportionately affects the poor, remains consistently negative. Anaemia is not just common; it is concentrated among the most disadvantaged.

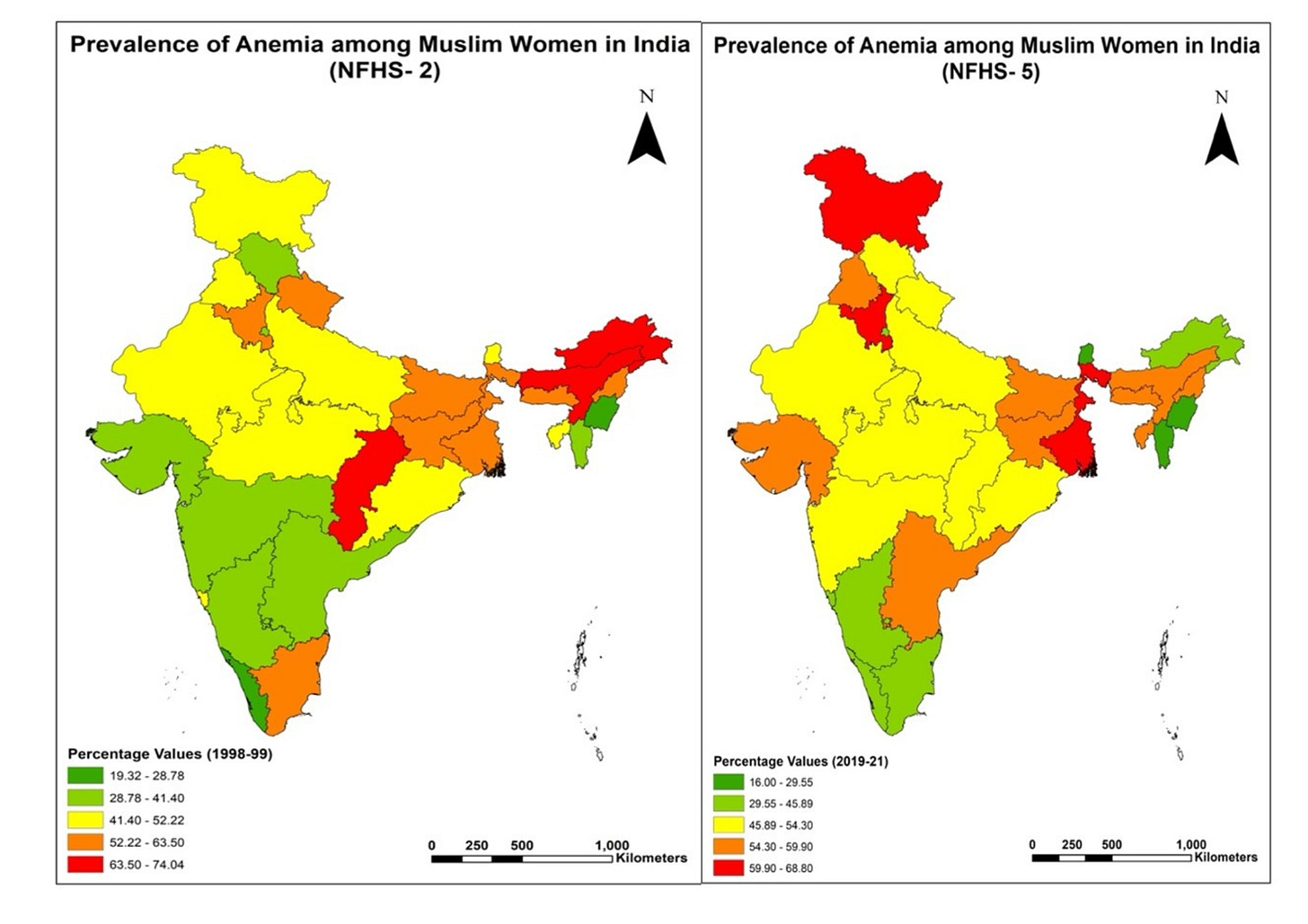

Geography further reinforces disparities. Eastern and Northeastern states like Bihar and Assam show the highest prevalence - above 60 percent in some districts. Southern and Western states fare better overall, but high-risk subgroups remain. Within states, rural Muslim women have about 8 percentage points higher prevalence than urban counterparts. In a state, districts with larger Muslim populations tended to have lower access to iron-folic acid supplementation and health awareness programmes. Cultural norms, low female autonomy, and limited literacy further constrain access, exposing systemic blind spots in service delivery.

Why This Matters Now

Anaemia is linked to fatigue, cognitive delays, and poor pregnancy outcomes; but it doesn’t just affect individual health. It impacts child nutrition, maternal mortality, learning outcomes, and economic mobility. For a group already facing reduced labour force participation and limited educational opportunities, these effects only deepen existing disadvantages.

The economic toll of anaemia is far from trivial. Studies have shown that it reduces productivity, earning potential, and leads to significant losses in GDP. Estimates by the World Health Organisation (WHO) suggest that every US$1 invested in reducing anaemia yields up to US$12 in economic returns. This makes a strong case for addressing anaemia among the most affected, such as Muslim women - not just as a health priority, but an economic imperative.

Muslim women’s health outcomes are rarely examined as a distinct category in mainstream policy debates. The resulting one-size-fits-all approach, which overlooks how religion, caste, poverty, gender, and geography intersect, comes at a cost: it impedes India’s commitment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 - especially SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality). Such blind spots carry a high price.

Programmes Exist, But Coverage Gaps Persist

India has launched several initiatives to reduce anaemia, notably AMB and Poshan Abhiyaan. These programmes have built valuable systems for micronutrient supplementation and outcome tracking, especially for pregnant and lactating women. Yet, the continued high prevalence among Muslim women suggests that design and delivery models are not reaching all.

Many programmes rely on Anganwadi centres or schools. These platforms often exclude out-of-school girls or those married early. As a result, adolescent girls in areas with low school retention remain unreached at a critical life stage.

Towards an Integrated Response

Sustainable progress against anaemia requires stronger and layered coordination. Targeting mechanisms within AMB and related schemes could prioritise SC and ST Muslim women in high-prevalence districts. Strengthening data systems to enable disaggregation by religion, caste, and geography will further support responsive interventions.

Platforms such as the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and the Public Distribution System (PDS) can be used to supply iron-rich foods and promote dietary diversity. Local health messaging, through community workers, NGOs, and even religious leaders, can improve acceptance and awareness.

Policy must also address adolescent girls more systematically. Expanding school-based supplementation, conducting regular health screenings, and incorporating nutrition education can help break the intergenerational cycle. Training frontline workers to recognise the social realities of Muslim women, such as restricted mobility, limited health literacy, and household decision dynamics, can strengthen inclusivity in service delivery.

Most importantly, anaemia must not be treated as a health-sector issue alone. It must be mainstreamed into the mandates of both the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and the Ministry of Women and Child Development through a coordinated strategy that combines clinical care, nutrition, and gender empowerment; while also addressing structural barriers like poverty, sanitation, and healthcare access.

Equity Is Not Incidental; It Must Be Intentional

The high rate of anaemia among Muslim women reminds us that national averages often conceal sharp social and spatial disparities. Seeing these gaps clearly, and designing for them explicitly, is a first step toward more inclusive public health systems. India has the data, the institutions, and the economic rationale. The next step is to connect these with purpose, through policies that recognise, prioritise, and adapt. Addressing anaemia among Muslim women is not just a health imperative. It is a test of India's commitment to leaving no one behind.

View as PDF

Authors:

The discussion in this article is based on authors’ research published in Frontiers in Nutrition (Volume 12). Views are personal.